Semi-natural landscapes

The semi-natural ecosystem types Boreal heath and Semi-natural grassland (meadow) are assessed as Vulnerable VU, while Coastal heath and Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow are assessed as Endangered EN. Tidal meadow is assessed as Vulnerable VU. Semi-natural grassland (hayfield) is assessed as Critically Endangered CR because the area of this ecosystem type has decreased substantially over the past fifty years. Semi-natural ecosystem types require correct care and management to maintain species diversity and ecological functions. The predominant impact factor affecting all assessed ecosystem types is changes in agriculture, which results in an absence of the traditional management practices required to maintain these ecosystem types.

- Innhold

- Description of semi-natural ecosystem types

- Assessed ecosystem types

- Ecosystem types on the Red List

- Impact factors

- Existing knowledge

- Expert Committe

- References

Semi-natural ecosystem types are formed by traditional agricultural management practices over a long period of time, and are dependent on this type of care to maintain the species composition and the ecological functions that are typical for these ecosystem types. Such ecosystem types are important for biological diversity in the agricultural landscape, but they also exist in urban environments, in heathland along the coast, in the mountains and in other uncultivated semi-wilderness areas referred to, in Norwegian, as "outfields".

Description of semi-natural ecosystem types

Semi-natural ecosystem types are formed by a protracted period of extensive and traditional agricultural management practices such as grazing, hay-making or heather burning. Areas may also have been cleared of rocks and forest, but the soil and vegetation have rarely been subject to regular ploughing, or altered by the use of pesticides, artificial fertilizer, or the introduction of new species. A special feature of the Norwegian landscape is the extensive historical use of uncultivated semi-wilderness areas ("outfields") for grazing and harvesting of fodder (Almås et al. 2004). Semi-natural ecosystem types therefore also exist in heathland along the coast, in forests and in landscapes associated with summer dairy farming in the mountains.

Extensive care and management is necessary to ensure that the species composition and the ecological functions that are typical for these ecosystem types are not lost as a consequence of succession and afforestation. Consequently, both a lack of management and inadequate management, for example weak grazing pressure, are threats to these ecosystem types. Intensification of farming practices with cultivation, sowing, use of pesticides or fertilising with artificial fertiliser or large amounts of manure is another threat. Large-scale changes in the environment such as climate change, air pollution and the establishment of alien species are also potential threats to semi-natural ecosystem types. However, over the past fifty years it has been a lack of management and the intensification of farming practices that has had the greatest significance for the loss of semi-natural landscapes in Norway.

Assessed ecosystem types

There are five assessment entities for semi-natural landscapes: Boreal heath T31, Semi-natural grassland (meadow) T32, Semi-natural grassland (hayfield) T32, Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow T33 and Coastal heath T34. In addition, Tidal meadow T12 is an assessment entity even though it is not a semi-natural ecosystem type. There are several reasons for this including the fact that there is an overlap in the existing data and impact factors for Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow and Tidal meadow. The assessment entities are major types as defined by Nature in Norway NiN (version 2.0) with the exception of Hayfields which are semi-natural grasslands with evidence of hay-making (SP-a) as a source of variation. Hayfields have been created as a separate assessment entity because the most important impact factor is the cessation of hay-making. Hayfields differ from the major type Semi-natural grassland (meadow) where the cessation of both grazing and hay-making can be important impact factors. In addition, Hayfields are assessed as having a higher Red List category than Semi-natural grassland (meadow).

Ecosystem types on the Red List

All five of the semi-natural ecosystem types are assessed as threatened: Hayfields are assessed as Critically Endangered CR due to the large reduction in area during the past 50-year period. The assessment of the expert group is that more than 80 % of the current area of Hayfields has seen a significant decline in ecological condition in the past 50 years when assessed against the ecological condition of Hayfields under traditional management. A lack of care and management or management which only encompasses grazing is the most important reason for a decline in the ecological condition of Hayfields. A reduction in area, combined with changes in biotic processes and interactions are also reasons for Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow being assessed as Endangered EN, and that Boreal heath and Semi-natural grassland (meadow) are assessed as Vulnerable VU. Coastal heath is assessed as Endangered EN because at least 80 % of the total area is degraded, and a decline in the ecological condition due to biotic changes is assessed as being greater than 50 %.

Impact factors

In the course of the fifty-year period which is the basis for Red List assessments, farming and the agricultural landscape in Europe and Norway have gone through massive changes. The transformation from extensive and traditional methods of operation in farming, to more intensive and effective operations, began as early as around 1900 but the changes accelerated from 1950 onwards (Emanuelsson 2009, Stoate et al. 2009). The intensification of land use led to a decrease in the overall area of semi-natural ecosystem types as a result of cultivation and the use of mineral fertilizer (Aune et al. 2018). In addition, more efficient agricultural production led to a number of less productive areas no longer being used or, to a lesser degree, being used as pasture for livestock. Semi-natural ecosystem types have therefore collapsed or have a degraded ecological condition as a consequence of traditional management practices either lacking or being insufficiently intense. In uncultivated semi-wilderness areas (outfields), the regrowth of forest has led to the disappearance of large areas of Coastal heath, Boreal heath, and Semi-natural grassland, or their likely disappearance (collapse as ecosystems) in the next 50 years.

Changes in the use of the landscape associated with summer alpine dairy farming require a special mention as these have a significant influence on the ecosystem type Boreal heath. This ecosystem type can be found across the entire country, but in southern Norway it is particularly associated with summer dairy farming areas in the mountains. Boreal heath is an open ecosystem type without tree-cover, dominated by dwarf bushes and heather1, requiring livestock grazing and clearing, or tree felling, to prevent forest regrowth. In areas surrounding the alpine summer dairy farms large amounts of wood were often removed for use in dairy operations. The traditional alpine summer dairy farms have declined from 1900 and onwards (Reinton 1955, Stensgaard 2017) but it has taken time for the impact of this to become apparent in the landscape in the form of vegetation changes and forest regrowth. Currently large parts of Boreal heath are no longer an integrated part of farming operations and are in the process of becoming overgrown due to low grazing pressure and a lack of clearing and tree felling.

A warmer climate will contribute to an acceleration of the forest regrowth process in all semi-natural ecosystem types where traditional agricultural management practices have ceased or are insufficiently intense. In addition, a warmer climate can provide alien species with improved opportunities to become established at higher latitudes and elevations (Forsgren et al. 2015). Semi-natural ecosystem types are particularly vulnerable to establishment by alien species (Eriksson et al. 2006, Jauni and Hyvönen 2012), particularly in the lowlands in parts of southern Norway (Daugstad et al. 2018). Establishment by alien species influences the competitive conditions and consequently the species composition in that competitive and fast-growing alien species outcompete species which are typical for the ecosystem types and which require a large amount of light (Didham et al. 2007). Alien pathogens that attack deciduous trees such as ash Fraxinus excelsior and elm Ulmus glabra can be a threat to those semi-natural grassland ecosystem types that have trees (i.e. wooded meadow and wooded pasture).

A typical feature of semi-natural ecosystem types is that the addition of nutrients via air pollution can have relatively significant consequences in these ecosystem types (Aarrestad and Stabbetrop 2019, Stevens et al. 2010, 2011). The calculations by Austnes and research colleagues (2018), show that 20 % of the land in Norway in the period 2012-2016 had atmospheric nitrogen depositions in excess of the defined tolerance level. Atmospheric nitrogen is a particular problem on the coast of southern Norway in areas with Tidal meadow, Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow and Coastal heath. The area with nitrogen pollution above the tolerance level has decreased from 30 % to 20 % in the period 1978-2016. Coastal heath, Lime-poor semi-natural grassland, and to a certain degree Intermediately lime-rich semi-natural grassland, are particularly vulnerable to impacts from air pollution (Aarrestad and Stabbetorp 2019).

Land conversion and land use change for purposes other than agriculture, such as housing and industrial areas, holiday cabin developments, and road-building, are also a threat in certain areas. Land conversion and other encroachments are particularly significant impact factors for Tidal meadow and Semi-natural tidal and salt meadow (Evju et al. 2015).

1. Areas of Boreal heath with calcareous (lime-rich) soils may have a greater number of meadow species.

Existing knowledge

In Norway we have neither precise information regarding the area of the assessed semi-natural ecosystem types, nor do we have comprehensive surveying or monitoring of representative areas that could provide a basis for estimating area, changes in area, traditional management or forest regrowth conditions. The assessments are therefore based on other available sources of information such as data from surveys of ecosystem types, Naturebase (Naturbase), ecological condition indicators in the Nature Index of Norway (Naturindeks for Norge), historical agricultural statistics, and results presented in scientific articles, as well as expert assessments. In assessing the impact factors we have relied upon published studies which are primarily from Norway, but we have also drawn on studies from neighbouring countries in the Nordic region where this has been relevant.

Nature in Norway NiN surveying, carried out on behalf of the Norwegian Environment Agency in the period 2014-2017, has provided useful information on the state of forest regrowth for several of the ecosystem types and is therefore part of the data on which assessments are based. Information from surveys of ecosystem types is used with care, partly because ecosystem type surveying is not set up for ensuring that the data is representative for the area being surveyed, and areas which are surveyed are not randomly selected. An attempt has been made to relate the assessments of the ecological condition of ecosystem types to the relevant variables in the descriptive classification system in NiN 2.0. The variables relevant to the assessments are primarily rapid regrowth succession in semi-natural farmland (7RA-SJ), the corresponding variable to describe the stages of succession in Boreal heath (7RA-BH), shrub layer cover (1AG-B), total tree-coverage (1AG-A-0) and actual intensity of use (7JB-BA).

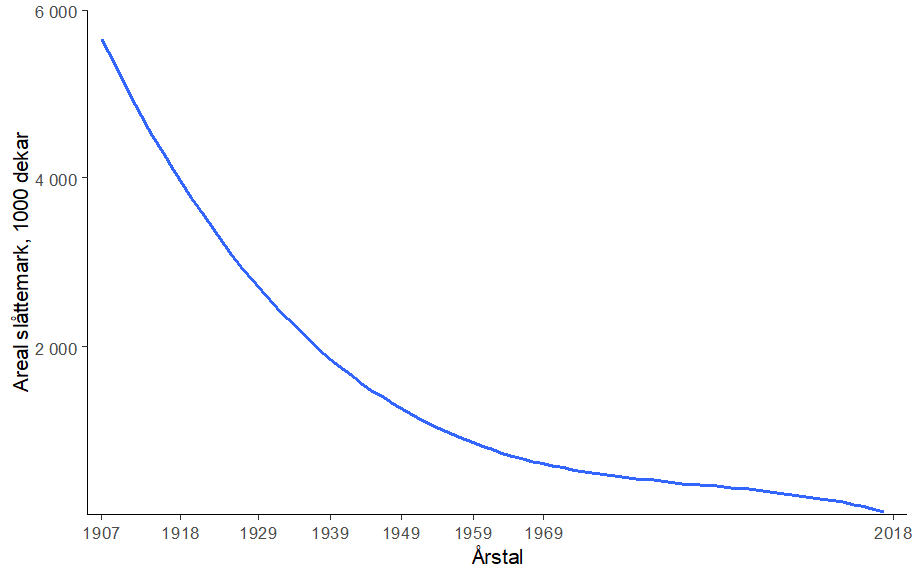

The Nature Index of Norway contains two indicators of the ecological condition of Semi-natural grassland (meadow) and Coastal heath (Johansen et al. 2014). The indicators in the Nature Index show a considerable decline in the ecological condition from 1950 and onwards to the present day. For Hayfields, the data and experience gathered during the development of the Action Plan for Hayfields is an important component of the existing knowledge base. Data has also been used for Hayfields from the official Census of Agriculture from 1907 and onwards to provide a rough estimate of developments in the size of the area with Hayfields. Based on the agricultural census, and information from the Action Plan for Hayfields, it is our assessment that it is likely that the area with Hayfields where management in the form of traditional hay-making is currently practised, is less than 1 % of the area with Hayfields fifty years ago. The area that can be classified as Hayfields would be larger than the area that currently has traditional management, but it is nonetheless likely that more than 80 % of the area with Hayfields has been lost in the past fifty years.

In the assessment of Boreal heath we have used information on the development of alpine summer dairy farms and grazing in alpine summer dairy farm landscapes. This information comprises statistics that show the development of alpine summer dairy farm use (Stensgaard 2017) and published results from a considerable number of of research projects where landscape and vegetation changes in the alpine dairy farm landscape have been studied (for example Olsson et al. 2000, Wehn et al. 2012, Wehn and Johansen 2015).

Information from Naturebase is used to obtain a rough overview of the geographic distribution of the ecosystem types.

Changes in the area of Hayfields based on the official Census of Agriculture from 1907 – 1969 and the estimated area of Hayfields as per the Management Plan for Hayfields in 2018.

Expert Committe

The members of the expert committee for Semi-natural landscapes were Knut Anders Hovstad (chair), Geir Arnesen, Line Johansen, Ellen Svalheim and Liv Guri Velle.

References

Aune S, Bryn A, Hovstad KA (2018). Loss of semi-natural grassland in a boreal landscape: impacts of agricultural intensification and abandonment. Journal of Land Use Science 13: 375-390.

Bratli H, Evju M, Jordal JB, Skarpaas O, Stabbetorp O (2014). Hotspot kulturmarkseng. beskrivelse av habitatet og forslag til nasjonalt overvåkingsopplegg fra ARKO-prosjektet. [In Norwegian.]

Bratli H, Jordal JB, Stabbetorp O, Sverdrup-Thygeson A (2011). Naturbeitemark - et hotspot-habitat. Sluttrapport under ARKO-prosjektets periode II. 714. [In Norwegian.]

Didham R, Tylianakis JM, Gemmell NJ, Rand TA, Ewers RM (2007). Interactive effects of habitat modification and species invasion on native species decline. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 22: 489–496

Direktoratet for Naturforvaltning (2009). Handlingsplan for slåttemark. [In Norwegian.]

Emanuelsson U (2009). The Rural Landscapes of Europe – How man has shaped European nature. Formas.

Evju M, Hanssen O, Stabbetorp OE, Bratli H, Ødegaard F (2015). Strandeng–et hotspot-habitat. Sluttrapport under ARKO-prosjektets periode III. 1170. [In Norwegian.]

Eriksson O, Wikström S, Eriksson Å, Lindborg R (2006). Species-rich Scandinavian grasslands are inherently open to invasion. Biological Invasions 18: 355–363

Forsgren E, Aarrestad PA, Gundersen H, Christie H, Friberg N, Jonsson B, Kaste Ø, Lindholm M, Nilsen EB, Systad G (2015). Klimaendringenes påvirkning på naturmangfoldet i Norge. [In Norwegian.]

Henriksen S, Hilmo O (2015). Norsk rødliste for arter 2015. Artsdatabanken, Trondheim. [In Norwegian.]

Jauni M, Hyvönen T (2012). Positive diversity-invasibility relationship across multiple scales in Finnish agricultural habitats. Biological Invasions 14: 1379–1391

Johansen L, Hovstad KA, Åström J (2015). Åpent lavland. Page 131 - In: Framstad E (ed.). Naturindeks for Norge 2015. Tilstand og utvikling for biologisk mangfold. Miljødirektoratet Rapport. [In Norwegian.]

Kaland P, Kvamme M (2013). Kystlyngheiene i Norge–kunnskapsstatus og beskrivelse av 23 referanseomrader. Oslo: Miljødirektoratet. [In Norwegian.]

Olsson EGA, Austrheim G, Grenne SN (2000). Landscape change patterns in mountains, land use and environmental diversity, Mid-Norway 1960-1993. Landscape Ecology 15: 155–170

Reinton L (1955). Seterbruket i Noreg Bind I. Aschehoug Co. (W.Nygaard), Oslo. [In Norwegian.]

Stensgaard K (2017). Hvordan står det til på setra? Registrering av setermiljøer i perioden 2009–2015. [In Norwegian.]

Stoate C, Báldi A, Beja P, Boatman N, Herzon I, Van Doorn A, De Snoo G, Rakosy L, Ramwell C (2009). Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe–a review. Journal of Environmental Management 91:22-46.

Veen P, Jefferson R, Smidt Jd, Straaten J (2009). Grasslands in Europe of high nature value. KNNV.

Wehn S, Johansen L (2015). The distribution of the endemic plant Primula scandinavica, at local and national scales, in changing mountainous environments. Biodiversity, 16(4), 278-288